The best of what Ireland offered in food and cooking was most evident in the celebration of feast and holy days.

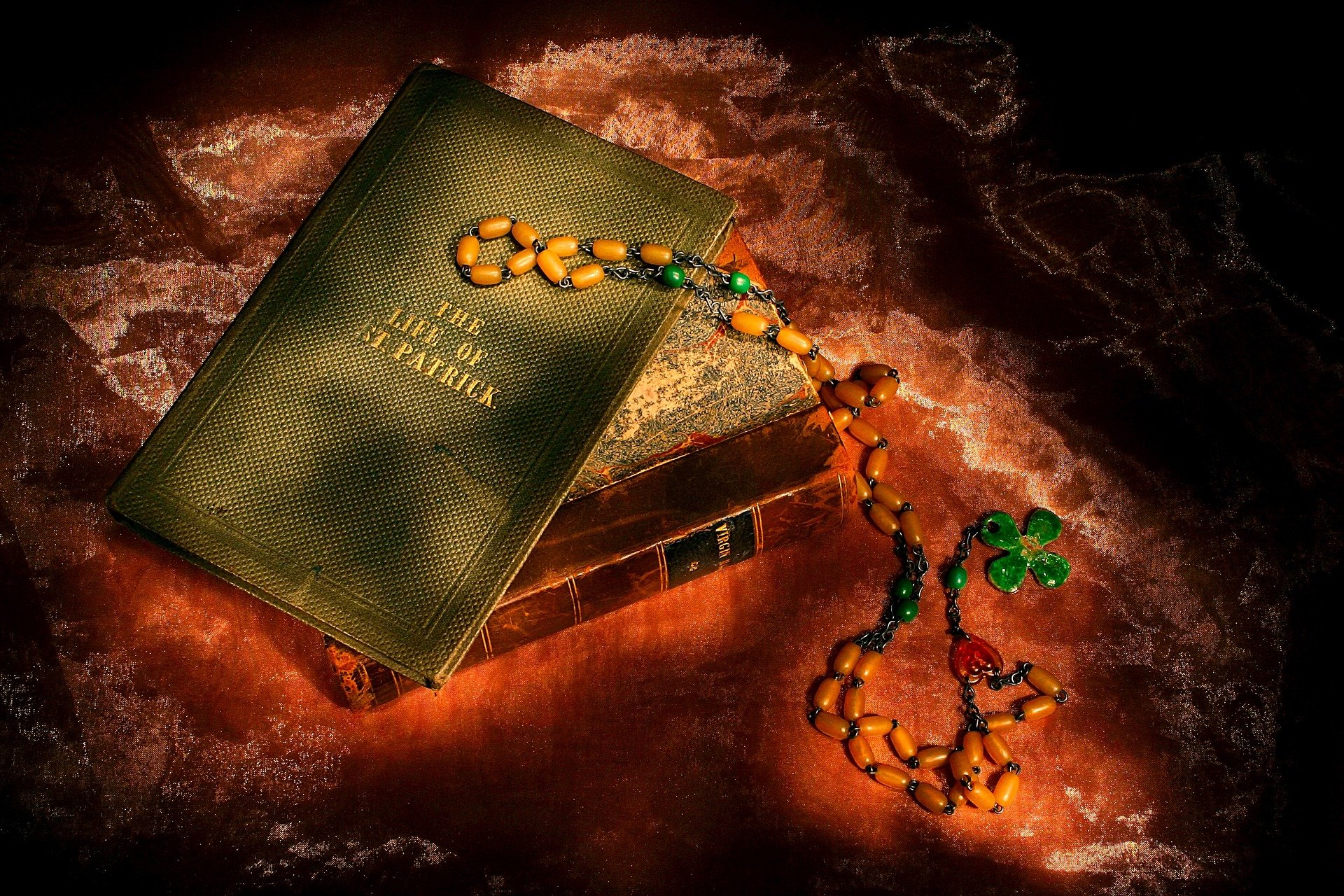

Halloween, as a secular festival, had a set package of festive foods and dishes like colcannon, nuts and fruit bracks. However, the gathering of food to the table on St. Patrick’s Day was of special significance especially as the holiday often falls during the Lenten fast. Saint Patrick’s Day gave the opportunity to break from the austerities of a fasting regime.

Meat made a return to the diet, if only for a day. The prohibition on eggs was also lifted for the day and those who abstained from alcohol were granted the one-day privilege of partaking in a celebratory beverage, the pota Phádraig, in honour of the Saint. In rural areas, meals of pork and bacon with potatoes and garden vegetable were common, while the cites and larger towns offered a diversity of goods from merchant and grocer shops.

Signature Foods & Dishes

PORK

There are a number of signature foods and dishes that may be identified as typically Irish and pork along with ham, bacon, pork puddings and sausages are amongst the meats most closely associated with Irish foodways.

From the prehistoric period through to the present day, pork and cured pork meats and products have held enduring popularity. Pork was a popular meat choice simply because the pig was an easy and profitable animal to rear and slaughter at home.

Traditionally, small rural households kept two pigs, one for the table and the other to go to market. Essentially, then, the pig was the ‘gentleman who paid the rent’ and the one who supplied the household with fresh and cured meat throughout the year.

In Ireland, the pork fillet is and was relished as one of the greatest delicacies the pig can offer. Indeed, the esteem in which this tender loin is held is clear in its popular name in Ireland; the pork steak. This cut was valued for not only for the quality and leanness of its meat, but in the scheme of traditional Irish agriculture, the pork steak represented much more, marking it apart as a luxury in a time when fresh meat, rather than the more everyday salted variety, came to the table.

For celebratory occasions, pork was an indulgence. If fresh meat was not available, home-cured hams and bacon were elevated to festive status and because these were close to hand, they became the meat associated with a special meal for Saint Patrick’s Day.

Potatoes

If ever there was an ingredient that could be held as an emblem for Ireland, it must surely be the potato. Since its introduction to Ireland in the early seventeenth century, it has become an intrinsic part of Ireland’s food culture with the Great Famine of 1845-50 marking a watershed in the history of modern Ireland.

The esteem with which potatoes are held has almost become part of the Irish psyche – everyone has an opinion on potatoes be they the first early varieties of summer or the main crop floury varieties of autumn. For many still, no meal is complete without the ubiquitous potato and no festive meal is set without an array of potato dishes – roasted, mashed, and creamed.

The enduring popularity of the potato is easily understood – potato cultivation is eminently suited to Ireland’s soils and climate. The national palate favours mealy, floury varieties, which are excellent vehicles for carrying the flavour of fat in the form of butter and cream.

Little wonder then that creamy dishes of colcannon and champ were considered festive dishes and the dishes brought to table for occasions of special celebration like Saint Patrick’s Day.

As an ingredient, the potato is not only palatable but it is highly versatile and traditionally it was used across the social spectrum in the preparation of potato puddings and potato breads. The northern counties in particular developed a distinctive baking tradition based on potatoes with potato breads, potato apple cakes and potato oaten breads a characteristic feature of these regions.

BREAD

The story of bread in Ireland is a fascinating one and as intricate as the many and varied factors that have shaped Ireland’s culture. Before the introduction of the potato, the oatcake was the everyday bread variety of the Gaelic Irish. Wheaten bread and loaves were more closely associated with the Anglo-Norman communities that largely settled in the Leinster and Munster regions of the island from the mid-twelfth century onwards.

The bread you ate therefore was a symbol of cultural outlook and aspiration. While white loaves of refined wheaten flour also differentiated the poor from the wealthy and the urban and the rural populations. The importance of the oatcake waned as the potato gained popularity amongst Ireland’s rural population from the mid eighteenth century onwards.

Bread played as secondary role and did not re-emerge as the staple until after the Great Famine of the nineteenth century. Post-Famine Ireland was therefore the era of great baking advancement in both the home and the commercial sphere.

It may be said that the Irish are at their most creative when it comes to home-baking and this tradition has been building since nineteenth century when soda bread and its making became part of the fabric of the woman’s working day.

This soft, cake-like bread was made with wholemeal or white wheat flour. For special occasions it was enlivened with fruit, spices, treacle, eggs and butter giving rise to a extended family of soda bread varieties – caraway sodas, fruit sodas or spotted dogs, treacle sodas, maize and wheat sodas and miniature soda breads in the form of plain and fruit scones.

Today Ireland is seeing a resurgence in small craft bakeries that turn out high quality yeast and sourdoughs. The status of soda bread, produced in the home or by artisan bakers, remains strong making enriched soda breads the ideal accompaniment to the festive table.

FISH

On Saint Patrick’s Day, 1829, Humphrey O’Sullivan from Callan in County Kilkenny enjoyed a festive dinner with the local priest.

He tells us of the day that ‘a jolly group of us drank our ‘Patrick’s Pot’ at the parish priest’s, Father James Henebry. We had for dinner fresh cod’s head, salt ling softened by steeping, smoke dried salmon and fresh trout with fragrant cheese and green cabbage.’

A veritable feast of fresh, salted and smoked fish at the one sitting and evidence of the bounty of Irish fresh waterways and seas. In Ireland however, the fish that enjoys greatest reputation is the wild salmon. For generations, it has been famed for its fine taste and nutritional qualities. It has become part of Ireland’s mythological and folk traditions.

Magical and health giving, the salmon was associated with saints and heroes in stories of ancient Ireland. The ‘king of the river and sea has, according to some studies been in Irish waters for at least 35,000 years. Throughout history, foreign visitors to the island have commented on its prevalence.

The Englishman, Arthur Young, for example, who travelled through Ireland in the late 18th century, said that in Ballyshannon, Co. Donegal, he was ‘delighted to see the salmon jump, to me an unusual sight. The waters were perfectly alive with them.’ Indeed, the salmon’s splendid jumping ability, according to folk belief, was bestowed upon it by Saint. Patrick. As a result, the saying, sláinte an bhradáin (the health of the salmon) was once a popular blessing of good health.

One myth about the fish that is familiar to every Irish school child is the story of Fionn Mac Cumhail and the magic salmon of knowledge. It runs as follows: When Fionn was seven years old, he met a seer on the banks of the River Boyne called Finneigeas, who had been trying for seven years to catch the ‘salmon of knowledge’, in order to gain boundless wisdom.

The seer had finally caught the fish, and entrusted it to Fionn for cooking, he warned him, however, not to eat a bit of it. While cooking the fish, Fionn burnt his thumb, which he immediately stuck in his mouth giving him the gift of wisdom and wondrous sight.

ALCOHOLIC DRINKS

The repertoire of Irish traditional beverages extends to ale, beer, stout, whiskey, flavoured whiskey, alongside apple and pear ciders. Many of these were routinely produced in a home setting until the emergence of the commercial breweries and distillers throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

However long before the commercial industry was established, Ireland had developed a reputation in particular for the quality and distinctiveness of its whiskey. Fynes Moryson, in the early seventeenth century considered Irish whiskey ‘the best drink of its kind in the world’.

He also refers to the distinctive Irish preference of flavouring whiskey with raisins and fennel seeds. Today Irish whiskey retains a distinctive character, which depends on production methods that vary from the distillation of single malts to blends to pure pot-stilled varieties.

Whiskey also comes in to its own in the celebration of Saint Patrick’s Day. Not only is it customary to toast the Saint with a glass on his feast day but also the spirit was also routinely used in the ritual of ‘The drowning the shamrock’.

At the end of the day, the shamrock, which had been used decoratively on a hat or coat, was removed and put into the day’s last glass of whiskey or tumbler of punch. When health had been toasted or the Saint honoured, the shamrock was picked out from the bottom of the glass and thrown over the left shoulder.

SYRUPS AND CORDIALS

Given Ireland’s extensive and diverse uncultivated habitats, wild foods have always played an important role in the diet and food patterns.

Depending on season, the wild offers up green leafy vegetables like wild garlic, delicately perfumed wild flowers like elderflower and wild rose and of course a myriad of wild fruits the most popular being wild and crab apples, elderberries, blackberries, bilberries, rosehips and haws.

These were sought after supplements to the more mainstream foods but they were also processed into preserves, syrups, and cordials to be enjoyed throughout the year. Many were also valued for their medicinal uses. In rural areas, kitchen gardens were well stocked with soft fruits like currants and raspberries and these too were used in the preparation of storeroom drinks.

In the big country houses from the eighteenth century onwards, the job of cordial and syrup preparation was a specialized undertaking. Here dedicated distil rooms or stillrooms were commonplace for the preparation of fruit and flower drinks and all kinds of sweetmeats.

The still room maid was responsible for their making. In recent times, there has been an enthusiastic resurgence in small-scale juice and cordial production and the country now has a impressive offering of apples juices and exquisite blackcurrant and elderflower cordials – prefect for a non alcoholic indulgence on the feast of Saint Patrick.

Explore & Book

Food & Drink Experiences

Vintage Afternoon Tea At Newbridge Silverware

What You’ll Get The Exclusive Good Food Ireland® Vintage Afternoon Tea Experience at Newbridge Silverware with a Museum of Style Icons visit & a 20% Discount Voucher for Newbridge Silverware Shopping Included, and free car parking. Domo’s...Craft Beer & Seafood Trail of Howth, Dublin

Craft Beer & Seafood Trail of Howth Perfect for the man in your life for Valentine’s Day. What better way to spend an afternoon, than eating the best locally caught Seafood in Ireland, washed down with an ample amount of local Craft Beer. Add...Majestic Afternoon Tea at the Maryborough Hotel – Cork

Perfect for Valentine’s Day. Upon arrival, be welcomed by the warm and attentive team at the stunning Maryborough Hotel and Spa in Maryborough, Cork. When making your reservation you have the wonderful option to take Afternoon Tea in the beautiful...